Art and Self-Direction

Thanks to Dr. Naomi Fisher for this guest post, which instantly rang true for me as someone who’s favourite thing to do growing up was to make art and is privileged enough to be surrounded by many talented and inspirational self-directed young artists who always know what they want to make. Young people who are used to having their ideas respected have a keen sense of when they are not, we adults would do well to listen to them. Naomi is a clinical psychologist, writer, advocate for self-directed education and author of ‘Changing Our Minds: How Children Can Take Control of their Own Learning’. Her children have always been self-directed and have experienced Unschooling at home, a self-directed democratic school in France and now attend a self-managed learning community in the UK. ~ Kezia, EKS

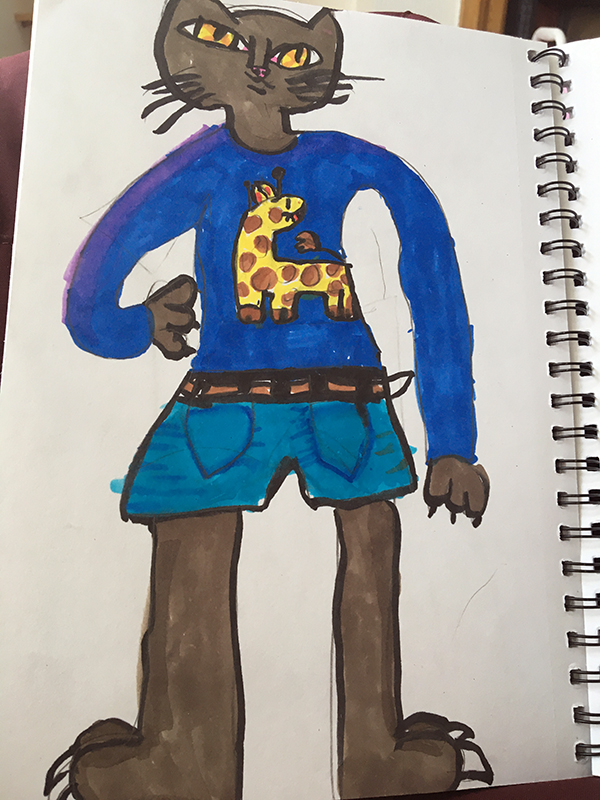

My daughter is an artist. Since she was very young, she has been drawn to the creative arts. She started drawing cats at the age of about three, even though we had no cats. She models figures out of plasticine and polymer clay. She made contraptions with lollipop sticks and material, explaining to me that of course it had no use, it was art.

She is drawn to art, and she spends hours most days doing art. At her self-managed learning setting, she makes art with other young people and with adults. There is a learning advisor, who is herself an artist. They work together. They make papier-mache cats.

Jessamy draws and makes art because she wants to do so. No one tells her what to draw, or how to draw it, unless she asks them to do so. She improves her technique by observing others, watching videos and experimenting. She has her own, distinctive, style which she has refined over years of practice. She still mostly draws cats.

So when I noticed that near to us there was an art class franchise, with sessions for children all the way through the week, I thought she might enjoy it. She agreed, and so I signed her up for a trial.

I was surprised when she came out in tears and when she told me she had been crying through some of the session. “What happened?” I asked. She explained that the whole thing had felt controlling. She had been told what to do, how to do it, and there was no scope for actual art at all. She felt the whole thing was pointless and a waste of her time.

I emailed the art teacher to explain that we would not be going back, and to say that Jessamy had not enjoyed the session. She wrote back saying that they had a an ‘objective and developmental reason’ for doing what they did. She said she thought that structure and a class style environment helped them to develop skills to do their own art later.

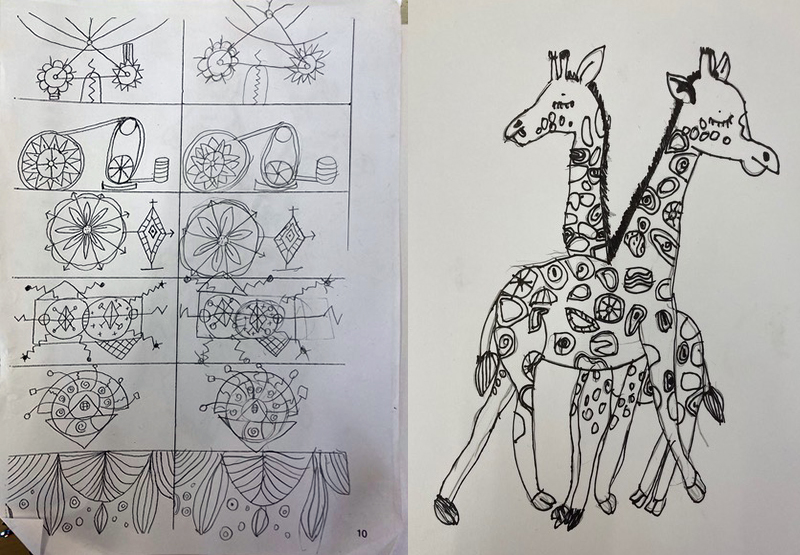

She attached some pictures of what she called Jessamy’s ‘lovely work’.

I had to laugh. I had never seen Jessamy produce anything like this before. Where were the cats? I showed them to her brother who laughed too. ‘That’s not her style at all!’ he said.

And then we realised that they were copies. She had spent most of the art lesson copying. That was what the art teacher meant by developing skills. Developing fine motor skills, by copying.

My educational choices for her flashed before me. My daughter had never before come across someone who expected her to copy things which she had no interest in, so she could learn some skills she might possibly use at some point for future art (perhaps when she moves on from cats to stylised giraffes or gears?). The whole concept was foreign to her. In her self-directed world, she learns because she needs to and wants to learn. She is entirely self-motivated. If she wants to develop her fine motor skills, she will do so, probably so she can draw better cats. Yet the art class – which was supposed to be a fun, out of school class – had completely removed her motivation by turning art into an exercise in following instructions and copying neatly. She found that so painful that it reduced her to tears.

This happens in school all the time. The art teacher isn’t unusual. She’s just working by school-based assumptions. School assumes that the best way to learn is by copying, and following a systematic set of instructions which will get you to some pre-determined standardised end. And by doing so the reason for doing it, the purpose and the drive, is lost. The joy is gone, forgotten in the enforced practice.

Most children get used to this early on, their training starts in reception or even nursery. They don’t cry any more. But it’s painful, nevertheless, this removal of purpose in a task. The reduction of learning to technical skills, repeated because the teacher told you to do it. Some children protest. Others give up.

It made me wonder what would have happened to my artist, had she gone to school. Perhaps she would no longer be drawing cats, and would have been ‘moved on’ by some well-meaning teacher. Or perhaps she would have lost her joy in drawing all together, whilst she followed someone else’s predetermined curriculum, carefully designed to develop her skills. I’ll never know. But I know one thing, we won’t be going back to that art class. We’ll spend the money on drawing paper instead, and keep on drawing those cats.

Lovely story. Here’s to many more cats (or whatever she’d like to draw)