This is the first in our series of articles for National Democracy Week 2018. Naomi Fisher takes a look at children’s rights in the context of a history of gradually extending democratic rights to ever greater portions of our society. For more articles about Democracy and Children see our campaign with The Phoenix Education Trust here. We’ll be publishing new articles every day this week, so keep a look out for more takes on this important topic.

This is the first in our series of articles for National Democracy Week 2018. Naomi Fisher takes a look at children’s rights in the context of a history of gradually extending democratic rights to ever greater portions of our society. For more articles about Democracy and Children see our campaign with The Phoenix Education Trust here. We’ll be publishing new articles every day this week, so keep a look out for more takes on this important topic.

It is a strange fact that even those who believe most passionately in democracy in all its forms, generally think that it should not be extended to children. Children, they say, can’t be trusted to make decisions about their lives, will vote on a whim, will not appreciate the complexity of various situations. If children have genuine power over their own lives, they say, the result will be chaos.

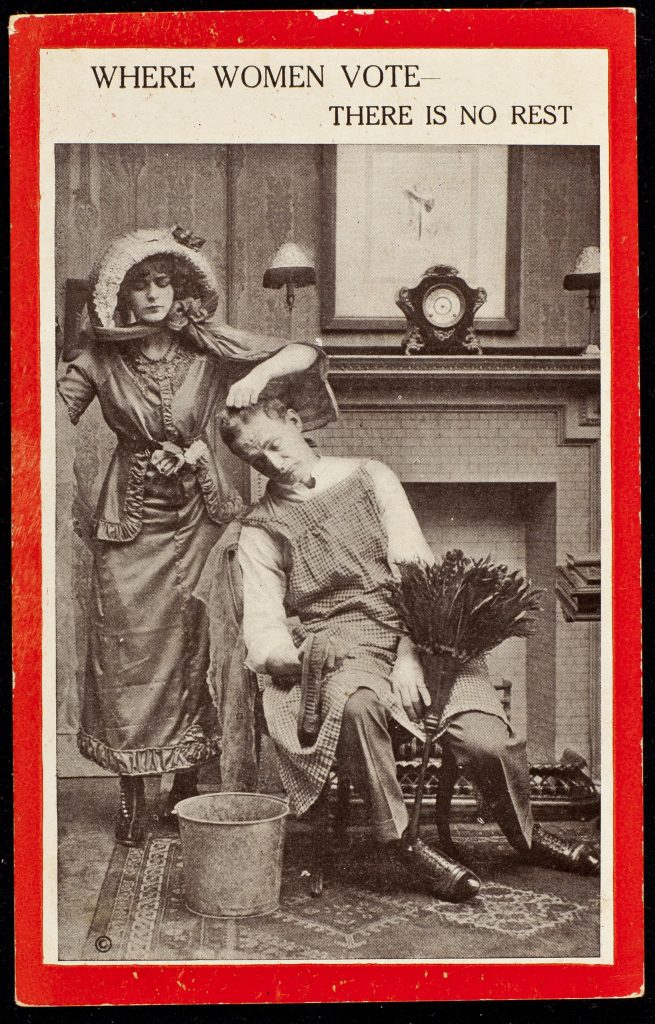

A century or so ago, this idea was extended to many sectors of society. Women, for example. Anyone who wasn’t a white, landowning male. And there were many people ready to stand up and explain why women should not be given power over their own lives,

“Women are tremendously accessible, extraordinarily impressionable, noted for the adoption of any new thing, and for the easy acceptance of other people’s views. Are those qualities which fit women to rule over the home and foreign affairs of a mighty empire?”

John Rees, MP for Nottingham East in 1917.

Their ideas were so convincing that many women themselves campaigned against women’s suffrage, saying that the responsibility would be too much, that women were ill-suited to making political decisions and that this would lead to the breakdown of society as we know it.

Their ideas were so convincing that many women themselves campaigned against women’s suffrage, saying that the responsibility would be too much, that women were ill-suited to making political decisions and that this would lead to the breakdown of society as we know it.

And of course in some ways it did. A society where women and men can both vote is a different one to a society where only men have that power. Laws are passed which would not have been passed if only men voted. If your aim is to retain power in the hands of an elite and maintain the status quo, then it makes sense to keep as many people without a voice as possible.

With children, however, we go a step further. Not only do we think they should be denied the vote, we also mostly believe that they should not have any choice over aspects of their own daily lives.

So much so, that many of us send them regularly to places where their clothing and food choices are strictly controlled, where they have no right to choose what they do or when they leave, and where there is absolutely no way of them changing the structures of the environment within which they spend the majority of time. We do all this, whilst telling them that it’s for their own good.

Perhaps it’s not so surprising, since most of us spent our childhoods being told that we couldn’t be trusted, that adults knew better than us, and that we needed to comply with adult demands and requests in order to live a fulfilled and happy life when we were grown. When we have our own children, we do the same with them. In fact, success at a conventional school is largely down to how well a child has complied with the adult demands around them, ignoring their own thoughts and desires in favour of seeking the approval of those in control.

Despite nearly a hundred years of democratic schools, for most people the idea of children making meaningful decisions about the school they attend, and what they do whilst there, is radical and frightening. When I have explained the idea to parents with children in conventional school, they have been incredulous and keen to tell me why it wouldn’t work. We asked the children at our school what they would like, said one mother. They said they wanted a swimming pool. She laughed. Clearly a swimming pool wasn’t on the cards.

When ideas are frightening, challenging to our whole world view, most of us react defensively. What would it mean if children actually could be trusted to make decisions about their own lives, and yet we are denying them that right? What would it imply for those who are investing thousands into putting their children into ever more controlling and monitored environments, schools which promise ‘excellence’ through an adult-imposed curriculum? What if a lot of the time and effort that we put into educating children is actually teaching them something quite counter-productive; namely, that what they think doesn’t count and that they can have no hand in shaping their environment?

You might be feeling the defensive thoughts come into your head right now. My children like school though, perhaps you’re thinking. Or My kids can’t be trusted to make decisions, they’d just watch Teen Titans all day. They need the structure of school. Or Children have no sense of what can be done, they don’t understand budgets and priorities. They need adults to take control.

Yet there are schools where children are making those decisions, every day. There are schools where the children and staff make all meaningful decisions together, even really important ones like which staff members should be employed next year, whether the school should move location and whether a child should be suspended or not. There are schools where the children are involved in the consequences for rule breaking, right up to suspension or expulsion.

Those children must be different to mine I hear you say. Mine can’t make decisions like that.

But what if what we actually mean is that we can’t trust children to make the same decisions that we would make for them? Like those men in 1917, we fear profound change and a loss of power, once we no longer assume that adults know best and should make all important decisions. We certainly can’t trust that children will make the same decisions as adults, just as in 1917 the men were right to fear than women wouldn’t make the same decisions as men. Their priorities might be a playroom rather than a science lab, a drum kit rather than a new computer for admin. And they might prefer to employ staff members who will play games all day rather than one who will instruct them in history and mathematics. A school where the children are involved in governance in a truly democratic way looks very different to one conceived and run by adults.

So it is true that democratic schools are radical and frightening. The very idea is deeply challenging to those of us who were schooled conventionally. So was woman’s suffrage in 1918. We can’t know what a future world would look like, where children grow up secure in their right to make decisions about their own lives and confident of their ability to affect change.

But we know what the alternative is, because we can see it all around us. Children who don’t have control over their lives, who are bored and frustrated and who are increasingly anxious, unhappy and under pressure.

I believe our role as parents is to sit with that uncertainty, and to acknowledge that fear of the unknown is not a good reason to deny our children control over their own lives. For perhaps, just perhaps, those children might have found a way to get their swimming pool, if the adults around them hadn’t laughed, and hadn’t taken their desire for one as a sign that they couldn’t be trusted to make decisions.

As it is, we shall never know.