ASD within democratic and self-directed schooling provision

This is an extract from an article first published in the Personalised Education Now Journal, Summer 2018, the full version of which will be available online here from the end of the summer.

A question I’m often asked in relation to autism and democratic and self-directed education is “but what about routine? How can this work without routine?”

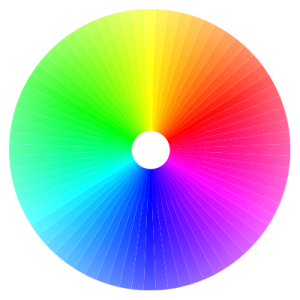

I want to be clear before I begin, that I don’t believe that there is a perfect school, or perfect approach overall. I do believe, very strongly, that there is a perfect approach for each child. That comes through knowledge, and understanding; and often trial and error. I have seen many systems work very well for students on the spectrum; because the spectrum isn’t, as we’re often taught to view it, linear. Personally I find the best way to view it is as a literal spectrum; a colour wheel. Points on the outside of this wheel denote particular skills; executive function; sensory needs; analysis; detail focus; social awareness. Along the “spokes” of this wheel our abilities can vary hugely; there can be huge contrasts between each skill set. We are not “low functioning” or “high functioning”. We each have highly specialised and different skill sets, just as all humans do; and it is the balance of those that helps to determine what kind of environment is likely to work for us.

I want to be clear before I begin, that I don’t believe that there is a perfect school, or perfect approach overall. I do believe, very strongly, that there is a perfect approach for each child. That comes through knowledge, and understanding; and often trial and error. I have seen many systems work very well for students on the spectrum; because the spectrum isn’t, as we’re often taught to view it, linear. Personally I find the best way to view it is as a literal spectrum; a colour wheel. Points on the outside of this wheel denote particular skills; executive function; sensory needs; analysis; detail focus; social awareness. Along the “spokes” of this wheel our abilities can vary hugely; there can be huge contrasts between each skill set. We are not “low functioning” or “high functioning”. We each have highly specialised and different skill sets, just as all humans do; and it is the balance of those that helps to determine what kind of environment is likely to work for us.

ASD often comes alongside an ability to focus intently and for incredibly long periods of time. This means that knowledge acquisition can be rapid, and subject mastery can come very quickly. But alongside these skills needs to come social balance.

Democratic and self-directed learning can provide both of these simultaneously. This form of democratic schooling provides the perfect ground for understanding the function of social rules and their creation as you actually see the rules evolving; you see the cause and effect happening in front of you, rather than not being part of the reasoning that led to the initial rules that you are simply told to follow, as within more conventional forms. In many schools the “existing rulebook” approach can be very challenging for students with ASD, as they will often want to apply all school rules very rigidly, as all that is available is the rule, without context; this can cause issues with relations with staff (the “little teacher” phenomenon) and with social interactions with students when the rules are applied rigidly to them. The setup of democratic schools, however, and the emphasis on the school community developing their own rulebook for community life demonstrates the context from day one.

Students see, in a concrete and understandable way, the process that leads from one student disturbing another, to the school meeting, to a discussion about why disturbing each other is upsetting, to the formation of a rule to deal with that, to the consequences that flow from it, to a continual demonstration of why and how emotions and logic have shaped the creation of this system. It’s logical, easy to breakdown, but still involves peer interaction and emotional intelligence to comprehend and apply the rules effectively. And these are skill sets that can and should be used and stretched, rather than simply defaulting to “Ah, X will never be able to understand this because he/she is on the spectrum.” It simply isn’t true. Yes, it depends on the individual skill set of each child, but within the right environment many of these soft skills can be acquired, both through opportunity and through the ability to self-regulate.

Which brings me on to self-directed learning and how that can potentially be incredibly beneficial. Students on the spectrum will have been internally managing their own needs throughout their lives. What we view as “not coping” is, in fact, the physical manifestation of a very sophisticated coping mechanism. Students who are stimming are often viewed as not coping, when in fact they are self-stimulating to soothe, to try and manage a challenging situation, or simply expressing happiness or excitement; us registering actions as out of the ordinary is simply that; it is us registering something different. More often than not we expect autistic individuals to adjust to a normative view of the world; to not employ the coping techniques that they have carefully developed. And yet we rarely ask ourselves to adjust to their needs when we view ourselves as more “flexible”. The usual reaction isn’t to acknowledge the stimming, check for any overly stressful situations and then just accept it, to the point that it isn’t even noticed other than as a peripheral “check”; but to try and stop the stimming in some way, when in fact it’s a deliberately compensatory reaction. We are happy to ask the child that we believe may be more rigid than us to change, but are not willing to change even our perception to enable their coping mechanisms.

Self-directed learning, in a somewhat contradictory fashion, provides security through providing more freedom. For those students whose abilities suit the model, the freedom from a “set” way of working provides the opportunity to take self-regulation and adjustment to a new level. A student who finds a room too loud or too bright for their liking can choose to move to another one, without fear of recrimination which would likely lead to an overwhelming anxiety as to whether to mention the sound/lighting. A student who wants to seek out social stimulation can do so; but can manage it by picking a chosen individual, rather than being limited by a class grouping, and can manage their own expectations and boundaries in that way. A student who wants to focus on their special interest can do; and in aligning with the democratic process (in requesting extra resources/events surrounding it) can not only discuss it in an academic and inter personal sense with peers, in an environment where they will be heard, but can also experience how the community experiences that special interest, from “I’m finding what you’re learning about fascinating, do you mind if I join in with you one day?” to “I miss you when you’re this focused on something. Can we make time to talk this week?”. Feedback of this kind, within a community of peers, is invaluable for all students to hear and be part of; but for autistic students it is, I believe, essential, as it provides them with a true reflection of their external selves whilst providing support and framing for internal growth.

Self-directed learning, in a somewhat contradictory fashion, provides security through providing more freedom. For those students whose abilities suit the model, the freedom from a “set” way of working provides the opportunity to take self-regulation and adjustment to a new level. A student who finds a room too loud or too bright for their liking can choose to move to another one, without fear of recrimination which would likely lead to an overwhelming anxiety as to whether to mention the sound/lighting. A student who wants to seek out social stimulation can do so; but can manage it by picking a chosen individual, rather than being limited by a class grouping, and can manage their own expectations and boundaries in that way. A student who wants to focus on their special interest can do; and in aligning with the democratic process (in requesting extra resources/events surrounding it) can not only discuss it in an academic and inter personal sense with peers, in an environment where they will be heard, but can also experience how the community experiences that special interest, from “I’m finding what you’re learning about fascinating, do you mind if I join in with you one day?” to “I miss you when you’re this focused on something. Can we make time to talk this week?”. Feedback of this kind, within a community of peers, is invaluable for all students to hear and be part of; but for autistic students it is, I believe, essential, as it provides them with a true reflection of their external selves whilst providing support and framing for internal growth.

We too often think of autism in terms of limitations, when in fact the skills and abilities of students are limited only by our perceptions. Viewing autism through a democratic and self-directed lens enables us to see what autism brings to a community and how it is enabled within it, rather than requiring it to be viewed in terms of difference that requires managing. Although it may appear contradictory, the emphasis on self-regulation and the freedom that enables that, can, for many autistic students, be the key to developing coping mechanisms and social skills that they will carry with them and develop further throughout their lives. But equally importantly, the students and community that grows up alongside them will also carry with them an understanding of autism without the tempering of an “othering”.

Communities like this function precisely through difference, critical thought and acceptance. These qualities play to the strengths of many autistic individuals; and through inclusion and understanding these qualities will also become present throughout the entire community. Self-direction and the use of democratic principles to underpin community interactions reinforces the value of individuals and the power of an individual voice; for many students with additional needs, this power can unlock strengths and nullify anxiety. For some autistic students, it can have the power to change everything.

Dear Helen,

Thank you so much for posting these wise words. I am so grateful to read this, as it puts in clear words what I have been trying for a long time to define for my two PDA daughters!